|

Context in UK

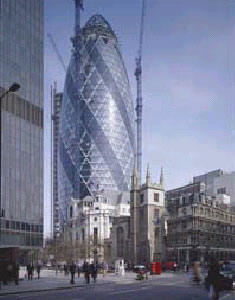

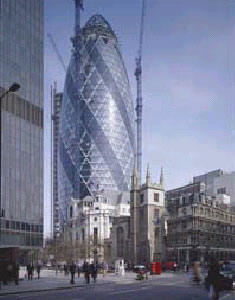

The skyline of London is responding dramatically to a recent wider

acceptance of high rise buildings, and new towers are sprouting up across

the city. In London there is a vociferous commitment from Mayor Ken

Livingston in increasing the density of the capital and building upwards.

The publicity surrounding the “Erotic Gerkin” by Norman Foster - with its

highly visible appearance to all London aspects but West London – means

that there is public interest in high rise design. Other high profile

towers include the elegantly profiled “Shard Tower” by Renzo Piano, which

has now received planning permission and will become London’s tallest

building.

Along with the increased desirability of high rise living there is a new

public awareness of designing buildings to a state of the art

environmental agenda. Although sustainability in housing has been an issue

for many housing providers for many years, projects like BedZed by Bill

Dunster (shortlisted for the Stirling Prize) has meant that an

environmental agenda is reaching wider public attention. Ken Livingston

also is promoting through the press the use of solar power for “LondON”

homes. After including photovoltaic panels on his own home, he is now

trying to change legislation to facilitate their use for all new London

homes.

With the surge in renewed interest in high rise living and in the tower

building type, architects are taking on the task of re-conceptualising and

re-imaging tower design.

Included in this section are some current UK based projects that are

promoting an innovative approach to high rise design. Although the

emphasis is on new build projects there is also much to be learned from

the debate and analysing their polemics, in terms of refurbishment

schemes.

Innovation in Environmental Strategies in Tower Design

A number of designers are recognising the importance of applying more

demanding environmental criteria on tall buildings design.

The advantages of a low energy / enhanced environmental performance are:

- Saving the environment and reducing building’s reliance on fossil fuels

- Financial incentives for the building owner / flat owner with reduced

energy bills

- Promotes image of the building – makes it more desirable

- Grants available for energy saving devices

Grant funding

With grant funding being offered for housing projects, there are financial

incentives to invest in energy saving devices. Some grants available for

housing schemes:

1. Energy Savings Trust – offers businesses and consumers a 50% reduction

on the cost of installing PV panels. This grant was used by Ken

Livingstone on his own house.

2. Clear Skies -- Initiative aims to give homeowners and communities a

chance to become more familiar with renewable energy by providing grants

and advice. Homeowners can obtain grants between £500 to £5000, whilst

community organisations can receive up to £100,000 or 50% of project costs

for grants and feasibility studies, whichever is the lower.

Innovations

Ken Yeang’s Bioclimatic Skyscraper

Ken Yeang’s research on the design of towers is key to any debate on the

subject as he sets out a polemic proposing that tower design is

climatically responsive. He advocates that a bioclimatic approach –

principles of designing with climate – be incorporated into tower design.

He has several books published and his architectural practice T.R.Hamzah

and Yeang International is designing tower projects, particularly in

southeast Asia. Ken Yeang has been involved in a new build tower in a

current redevelopment for Elephant and Castle.

In his book “The Skyscraper Bioclimatically Considered” Ken sets out a

polemic that intentionally diverges from skyscraper designer Louis

Sullivan’s essay with the similar title “The Skyscraper Aesthetically

Considered”.

This book is intended as a design primer where he proclaims that the

Bioclimatic Skyscraper is a new genre of the tall building type. Eclectic

and inclusive, the book enthusiastically covers a wide range of topics

with discussions, solutions and images. His approach is radical in the

sense that he has taken a known methodology – bioclimatic design - and has

creatively applied this to the tower block in a manner that has not been

undertaken.

At the outset Ken Yeang identifies the positive benefits of a bioclimatic

approach and a radical rethink in use of finite resources: reduced impact

of the building on the environment; reduced financial costs and energy

expenditure; healthier and more comfortable internal environment. He takes

basic considerations of the tower design and re-assesses them with this

new criteria. He questions some of the assumptions made in the design of

conventional towers and re-thinks these in an innovative way, always

minimising the building’s dependence on finite energy resources.

Some of the issues he covers which are common to any tower design are:

- plot ratio and orientation on the site

- floor plate design including vertical circulation and core design

- natural ventilation / sunlight to core

- building envelop

- fresh air design

- interstitial spaces like skycourts, atria, wind – scoops

- internal partitioning and services location

- vertical landscaping

Much of the focus of Ken Yeang’s research is on the design of new build

tall skyscrapers located in warm tropical climates as found in Southeast

Asia, whose extreme climate has incurred a heavy reliance on air

conditioning. With overheating becoming an increasingly important issue in

the UK, passive cooling is key for northern climates too. Devices like

wind scoops, sun shades, air infiltration shields, planted cooling walls,

responsive cladding, are all components that can be used in conjunction

with UK towers to provide improved comfort and save on energy use.

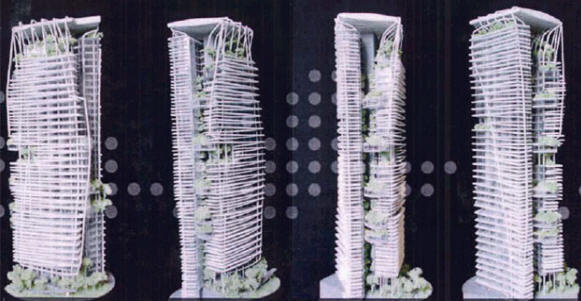

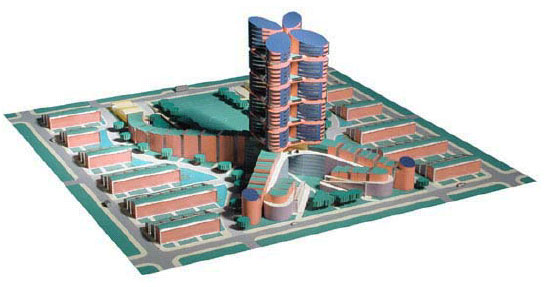

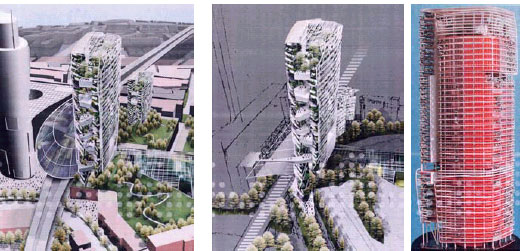

T.R.Hamzah and Yeang’s Tower at Elephant and Castle South London

Ken Yeang has been designing a tower as part of the major regeneration of

the Elephant and Castle area in South London. His proposal is for a single

tower of Residential use above a dense retail and commercial area. The

project is currently on hold.

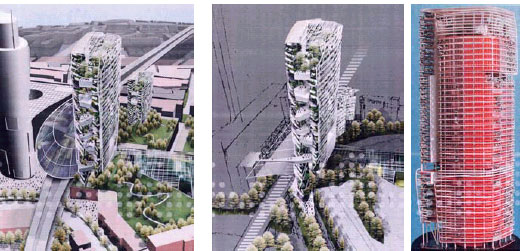

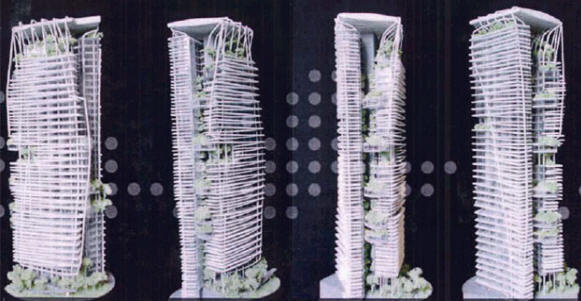

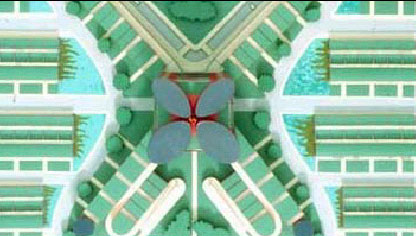

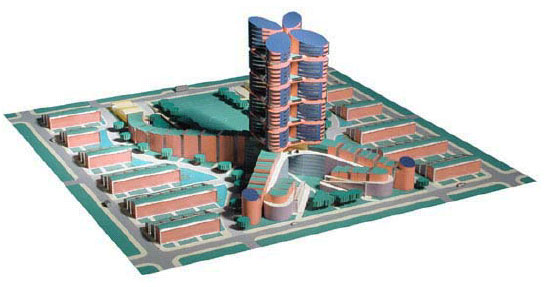

Bill Dunster’s Flower Tower

Bill Dunster is a pioneering British architect whose admirable aim is to

create carbon neutral cities through the design of energy efficient

buildings at the same time as making a low impact lifestyle more

attractive and convenient. He uses the word ZED in every project he is

involved in. This is an acronym for ‘Zero Energy Development’. His most

celebrated work to date is the BedZed project, which narrowly missed out

on 2003’s Stirling Prize.

BedZed is a mixed development urban village for the Peabody Trust. Located

on a brownfield wasteland site in the London Borough of Sutton, the

development provides 82 dwellings in a mixture of flats, maisonettes and

town houses, combined with workspace/office and community accommodation

including a health centre, nursery, organic café/shop and sports club

house.

The scheme incorporates numerous energy-saving strategies. The combination

of super-insulated units, a wind driven ventilation system, incorporating

heat recovery, photovoltaic panels, and passive solar gain stored within

each unit thermally massive floors and walls, considerably reduces both

electricity and heating requirements. Requirements are further reduced by

the scheme’s 135kW wood-fuelled combined heat and power plant.

Working alongside developer, Bioregional, Dunster also attempted, where

possible, to establish the specification of locally produced materials and

components, along with the sourcing of local labour, thus stimulating the

local economy, maximising urban / rural links and minimising pollution

from transportation.

Although the project is low – medium rise in nature, the sustainable

concepts that inform the scheme can also be used in high rise

developments. Indeed, this is now an area that Dunster is actively working

in. This can be seen in his latest speculative work known as the Flower

Tower or SkyZED.

Dunster states ‘We were worried… about the possible overall negative

environmental impact of conventional residential tower blocks, so we

decided to work on a concept mixed-use tower community that actually

generated its own energy’.

The Flower Tower incorporates most of the BedZed green strategies,

combining residential, work and leisure environments to minimise travel

and therefore transportation energy. Broadly speaking the first six floors

at the base of the tower house workspace and community facilities,

including schools, nursery facilities and a car-pool, while the

residential units occupy the floors above. Park and sports facilities are

placed in the ‘shade zone’ of the tower. Views, daylight and privacy are

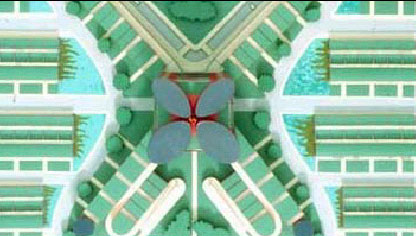

optimised by a four-petal shaped floor plate.

Dunster has conceived the tower as working like a ‘living machine’. He

claims that the scheme will reclaim all grey and black water for the

entire urban block while the permeable nature of the building will

minimise downdraughts, while effectively utilising wind to generate green

electricity. The combination of wind devices and photovoltaic components

mounted in the cladding and at roof level will allegedly meet the scheme’s

annual electric demand. Heat would be generated by either woodchip boilers

(for smaller schemes) or through the incorporation of a biomass fuelled

c.h.p. plant in larger tower developments.

Dunster states that the petal shape magnifies ambient windspeed by up to 4

times, meaning that vertical axis drag type wind turbines are a viable

proposition. The turbines envisaged for the flower tower projects are like

those designed for oil-rigs – they have self-lubricating bearings, rotate

almost silently and operate on a 5 yr maintenance cycle.

In terms of construction, Dunster envisages that the tower is mainly built

from reclaimed low-cost materials, such as slip formed ggbs concrete and

reclaimed timber stressed skin panels. The project would also use some

new, renewable, materials such as ply (presumably en ‘eco-ply’ like that

used at BedZed) and composite timber products such as glulam structures.

In terms of the tower’s shell, windows would be triple glazed and walls

would contain up to 300mm of insulation. This means that thermal

protection is maximised against both heat gain in the summer and heat loss

in the winter, and high levels of acoustic isolation could be expected.

In terms of residential mix, Dunster envisages a mixed community of two

bed, one bed and three bed maisonettes, which would enable a range of age

groups and, presumably, tenure arrangements.

Like Yeang’s towers, Dunster enlivens these residential areas with the

incorporation of communal sky gardens, thus enabling possibility for

high-level breakout space and social interaction. These are included at

every fourth floor and link all four accommodation wings.

Dunster’s ideas are, at present, for new-build projects but they have

relevance to the refurbishment of tower blocks, especially with regard to

the incorporation of CHP, PV and wind technology. The use of reclaimed

and/or low-embodied materials is also pertinent. This project for

live-work communities has made a green lifestyle more attractive and has

generated a positive image for sustainability in housing.

Innovation in Promotion of High Rise Living

Tackling issues as diverse as image of high rise living and apartment

tenure, designers, developers and housing associations are working to

transform the poor image that towers have suffered from. This innovation

is coming in both refurbishment and in new design. Refurbishment has

focused on making existing blocks work well in terms of basic services as

well as sustainability (see ‘current trends’ section). The best

refurbished blocks are now proving very popular, especially as homes for

older people.

The new-build proposals are of a different order. They are eye-catching

and headline-grabbing and offer a very 21st century approach to urban

living.

Barfield Marks’ SkyTower

Famed for their ‘London Eye’ project, architects Barfield Marks are behind

a new residential proposal, ‘Skyhouse’. This is a conceptual vision for a

new-build 30-50 storey super tower block. As their website states,

“Skyhouse is not another form of tower block. Skyhouse is a 21st century

building concept based on the principles of high quality design and

construction, clever use of space, and a major emphasis on ensuring the

building and environment is one where people want (as opposed to have) to

live. Integrating in a tall building a wide range of housing types and

sizes with shops, health clubs and gardens, Skyhouse uses green technology

– renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, recycling systems, high

insulation and low heat demand to reduce costs and conserve the

environment – to provide homes for the future; the future way to live.”

The sky-house scheme in effect challenges the numerous private sector

property developers who are reluctant to mix social housing, key worker

housing and privately owned property. As Julia Barfield comments “We need

to break down social divisions in this country. We need to create a more

cohesive society where different tenures are indistinguishable. We do not

want to repeat the mistakes of the Docklands where luxury private flats

stand next to council housing, but they may as well be miles apart.”

To this end, Barfield Marks have consulted Hyde Housing, who have

undertaken successful schemes where privately rented flats mixed alongside

social housing. Indeed, in a recent tower block scheme, Hyde rented out

flats at the top of the tower at market rents, which provided extra

capital to fund a concierge and refurbishment for the rest of the

building.

In addition, and like Dunster’s Flower Tower, the project would

incorporate a range of renewable energy mechanisms, such as wind turbines

and PV cells, which would provide energy to communal areas such as the

heating of a swimming pool.

Both socially and environmentally, the project incorporates a vision which

could be translated into the refurbishment of tower blocks.

Innovation in Building High Rise Towers

Although the technology to build upwards was developed early in the 20th

century, there have been more recent developments in construction and

detailing of towers. Modular off-site construction of building components

for towers was used extensively in the construction of UK towers in the

1960’s. Their subsequent defects, often due to hasty construction and poor

installation, meant that “prefab” or modular off site construction was

dropped from use. However in the last decade there has been a renewed use

of this construction type as its benefits have been recognised: speed of

construction, greater quality control in factory conditions and less

material wastage. Peabody Trust is a housing association that has

commissioned a number of projects adopting this type of construction.

There have been developments, too, in cladding technology and the ability

to modulate the interior environment through the building’s skin.

Offsite Prefabrication of Modular Units and Components

Offsite manufacture of residential units

Cartwright Pickard, a London based practice, have been causing a stir with

a series of innovative housing projects. Perhaps their best known project

to date is Murray Grove, London N1. Designed for the Peabody Trust, the

scheme is a city centre block containing 30 one and two bedroom units for

renting which targets young, single people on a modest income, who don’t

qualify for social housing.

Highly innovative construction techniques. Each flat is built up out of

two or three factory-finished steel framed modular units, delivered to

site complete with fittings, plumbing, wiring and carpets, and constructed

on site in just 10 days.

Thermal and sound insulation, fittings and finishes are all to a very high

standard, and the project has been specified to a ‘lifetime homes’

standard.

Pre-fabricated units could offer benefits to the refurbishment of tower

blocks. Blocks could be reduced to their shells and then units inserted as

required. This is positive as it enables the buildings to be flexible

enough to adapt to future uses.

Offsite Manufacture of Modular Components

There are a number of “prefabricated” building systems being adopted in

current projects. One system is in concrete, another system is in timber,

which has a far improved environmental performance than concrete. The

system consists of cassettes of wall, floor and roof panels which are

assembled on site – this has been used on many residential projects by

practices, like Architype (who partnered the development of the system)

and Sergison Bates. Architype now have a new build medium rise “tower” of

6 stories of student housing in timber panel under construction.

Innovations in Façade Technology

Double-skin façades

As indicated by the term “double-skin” such a façade is intended to mean a

system in which two "skins" - two layers of glass - are separated by a

significant amount of air space, that is to say, a second glass façade is

placed in front of the first. These two sheets of glass act as an

insulation between the outside and inside enabling the air to circulate

between the cavity of the two facades skin providing good air circulation,

thermal and accoustic performance, etc. The type of double-skin façade

then determines the type of air circulation. Of course, the most

interesting systems are those designed in such a way that in addition to

permitting natural air circulation, they also use solar energy, converting

it into electrical energy. As indicated by the term “double-skin” such a façade is intended to mean a

system in which two "skins" - two layers of glass - are separated by a

significant amount of air space, that is to say, a second glass façade is

placed in front of the first. These two sheets of glass act as an

insulation between the outside and inside enabling the air to circulate

between the cavity of the two facades skin providing good air circulation,

thermal and accoustic performance, etc. The type of double-skin façade

then determines the type of air circulation. Of course, the most

interesting systems are those designed in such a way that in addition to

permitting natural air circulation, they also use solar energy, converting

it into electrical energy.

Self-cleaning technology

Several approaches have been made in recent years to fight dirt build-up

on roofs, facades and windows. Self-cleaning coatings are improving

constantly. Window manufacturers can be very demanding when it comes to

the quality of the coatings. Not only maintenance of the facades must be

minimized by the self-cleaning function, but durability for the lifetime

of the facade, optical quality and scratch resistance are equally

important. Currently, there exist two main categories of self-clean

coatings: hydrophobic and hydrophilic.

Hydrophobic: Hydrophobic coatings repel water and dirt and prevent water

drops from drying on the glass pane and leaving ugly stains. The biggest

problem of this type of coating is that most hydrophobic coatings do not

exhibit enough hydrophobicity (contact angle with water > 1500) for the

self-cleaning effect to work. These coatings are often termed easy-clean.

Hydrophilic: It literally means 'attracting w ater', and is the opposite of

'hydrophobic' (water-repellent). That makes water droplets spread out,

across the surface of the glass. Basically, it means water spreads evenly

over the surface of the glass to form a thin film that washes away and

dries off quickly without leaving unsightly 'drying spots'. Hydrophilic –

water attracting - coatings can be photocatalytically active and break-up

organic dirt, which can be washed away by the water-sheeting effect on

hydrophilic surfaces. Hydrophilic coatings are mechanically much more

stable. They face challenges by metal ions from rainwater poisoning their photocatalytic activity over time and some also exhibit a certain

colour

tint. ater', and is the opposite of

'hydrophobic' (water-repellent). That makes water droplets spread out,

across the surface of the glass. Basically, it means water spreads evenly

over the surface of the glass to form a thin film that washes away and

dries off quickly without leaving unsightly 'drying spots'. Hydrophilic –

water attracting - coatings can be photocatalytically active and break-up

organic dirt, which can be washed away by the water-sheeting effect on

hydrophilic surfaces. Hydrophilic coatings are mechanically much more

stable. They face challenges by metal ions from rainwater poisoning their photocatalytic activity over time and some also exhibit a certain

colour

tint.

Photovoltaic glass

Photovoltaic glass is a special glass with integrated solar cells, to

convert solar energy into electricity. This means that the power for an

entire building can be produced within the roof and façade areas.

The solar cells are embedded between two glass panes and a special resin

is filled between the panes, securely wrapping the solar cells on all

sides. Each individual cell has two electrical connections, which are

linked to other cells in the module, to form a system which generates a

direct electrical current.

Current Trends in Refurbishment

Towards Sustainable Communities

A central issue that is now at the heart of the regeneration debate is the

Government’s

‘Communities Plan’, launched in on February 2003 and defined in the

document “Sustainable Communities: Building for the future”.

The Communities Plan

This Plan sets out a programme of action “for delivering sustainable

communities in both urban and rural areas”. It has three key themes, all

of which are very relevant to the sustainable tower blocks debate: one is

to increase the supply of housing in the South East, the second is to

tackle low demand in specific parts of the country, and the third concerns

the quality of public spaces.

It seeks to deliver not just “a significant increase in resources” but

also “major reforms of housing and planning” and “a new approach to how we

build and what we build”. The total budget fro the programme is c. £22

billion over three years: key elements include;

• £2.8 billion to bring council homes up to a decent standard.

• Investing £5 billion over the next three years to regenerate deprived

areas.

• An extra £201 million to improve parks and public spaces.

• Investing £350 million to speed up and modernise the planning system.

• £610 million for the growth areas.

• £500 million to tackle low demand and abandonment issues.

The Plan has received some criticism for failing to address sustainable

development issues, despite it’s title, but it has created a new focus on

the phrase ‘Sustainable Communities’ which provides a framework within

which sustainability practitioners can work with regeneration issues. The

focus on public spaces is also welcome: too often the spaces around tower

blocks are depressing and featureless if not seriously degraded.

Housing Bill / Housing Green Paper

For social housing, the key elements of the Housing Green Paper were as

follows:

• Continuing the transfer of stock from local authorities to housing

associations.

• A stronger strategic role for local authorities in long-term planning to

meet housing need.

• Reform of lettings policies to give more weight to tenants preferences

about where they live.

• Giving higher priority to homeless people the allocation of social

housing.

• Options for new flexibility to allow social landlords to make better use

of their stock in areas of low demand – for instance to meet the housing

needs of students or key workers.

• More emphasis on mixed tenure to help create sustainable communities.

Addressing the housing shortage

This is the most controversial aspect of the plan, due to its call for

major new development in the South East, primarily in the "growth areas"

(Thames Gateway, London-Stansted-Cambridge corridor, Ashford, and Milton

Keynes-South Midlands). Concern over building on green field and green

belt sites has led to opposition and has also focused attention on

building high-density settlements, as far as possible within existing

urban areas. Indeed some of the leading proponents of the plan have been

vocal in attacking ‘suburban sprawl”. The ODPM have stated that

developments not meeting density standards in the South East will be

called in. This of course focuses attention on high-rise dwellings and

makes the current work very relevant.

Addressing low demand

Around one million homes in parts of the North and Midlands are suffering

from low demand and abandonment. The Communities Plan has set up nine

‘pathfinder’ schemes in the areas worst affected with a view to tackling

the problems. Quite how this will be done remains unclear. Some experts

and politicians call for wholesale demolition to substantially reduce

housing stock but others talk of radical refurbishment and better

communications and links to areas nearby where there are employment

opportunities.

Inevitably unpopular housing in these areas will be high on any demolition

list and it is likely that some tower blocks will be on that list. While

there have been calls from those working on sustainable towers to halt

unnecessary demolition in favour of refurbishment it is unlikely that a

case would be made for towers on urban fringes in these pathfinder areas.

It is however worth noting that some of the pathfinder areas such as parts

of Birmingham and Manchester are relatively near economically successful

areas and the potential to turn these around may be much higher than those

in towns in areas such as north-east Lancashire. If money is available for

effective refurbishment then the blocks could certainly play a part in

regeneration.

Refurbishment examples

Most refurbishment is being run by local authorities and regeneration

partnerships, and as such is limited by available funds. Several

architects have expressed frustration at being unable to find the

resources to incorporate leading-edge sustainable development ideas such

as water harvesting and photo-voltaics, but the focus on what works for

residents is doing a lot to make blocks more acceptable and even

desirable. A few high-profile projects have led the way, among them the

increased public interest in Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower beside the

Westway, while the INTEGER Consortium are currently working ona very

detailed refurbishment to highest feasible standards of the Glastonbury

Tower in Pimlico.

The examples below are not detailed case studies, nor are they costed.

They are here to illustrate the range of approaches to refurbishment that

are currently going on in the UK and abroad.

Holly Street, Dalston, London

Catalyst: This was a regeneration initiative in the area which required

community involvement and consultation with tenants. Issue-based

sub-groups (including older residents’ concerns) formed out of which grew

a community trust – the Queensbridge Trust. Part of this process was

consultation and decisions about housing. Originally residents wanted all

towers demolished but it emerged that the older tenants liked tower block

living as they considered it safe and spacious. One tower block needed to

be kept to meet housing density requirements.

Focus: Residents were very involved in design issues and insisted on a 24

hour concierge. Office spaces and new shops at sub mezzanine level were

proposed which would pay for the overheads of security and maintenance.

However the project was costed at £10m for 119 units which was expensive.

Queensbridge Trust was the spur for lots of initiatives: strong focus on

training and community businesses – cleaning, minor repairs, landscaping,

concierge. They started winning contracts for these works from the

landlord. A ‘Job Link’ by local people for local people was established. A

Sports and Community Centre with IT suite and a community café was built

into the project. To combat problems of safety, a central square was

designed with secure play areas. A Residents room was also proposed in the

tower for informal socialising.

Five towers, Camden, London

Focus: A regeneration package has been proposed for 5 towers in Camden.

This is one of 8 DETR pilots using PFI for social housing. A Private

sector company was awarded ‘Facilities Management Contracts’ where the

deal is that they undertake big capital improvement projects early on and

then get to sell services to residents for the following years. They would

be penalised if their performance was judged below par by the tenants.

This big project has descended on the residents who are now getting up to

speed with the regeneration process. There are two residents from each

block who are on a residents’ steering committee. Previously tenants’

activity was minor and was limited to repair issues within each block. The

Tenants’ committee has decided it wants to broaden out the agenda to take

in training, employment, mothers and toddlers, etc. They are now about 6

months into the process and there 18 months of consultation to follow.

Appletree Court, Salford

Catalyst: A tenants association was formed in 1988 at Appletree Court in

Salford with an aim to reduce the social tensions prevalent in the estate.

Over the years this forum for social interaction also gave residents a

forum to talk about concerns, notably repairs, maintenance and management;

and they began to take more of a concerted interest in these matters and

also approached the local authority with their issues. In 1993 they formed

a tenant management company. They decided to do this on the basis that

“we’d be able to sort it out ourselves instead of having to wait for the

council” (i.e. repairs). In 1996, the newly formed management company

spearheaded by the tenants teamed up with Tony Milroy of the Arid Lands

Initiative and begun to transform the grounds.

Focus: The tenant management company took responsibility for maintenance,

repairs, lettings and ground maintenance. An Urban Oasis began to emerge

involving successive projects on the grounds. The starting point was the

erection of a fence to provide security and eventually led to the building

of a café and a vandal-proof conservatory.

.

The refurbishment of 7 tower blocks in Sheffield,

The impact of the refurbishment project of 7 tower blocks in Sheffield was

a small reduction in the energy consumption, a larger reduction in

emission of greenhouse gases, a big improvement in residents’ warmth and

comfort and an associated improvement in residents perceived health

status. There was a significant negative impact on resident's financial

status due to the large rent increase used to pay for the improvements.

Some of the issues that the study undertaken by Sheffield Hallam

University included financing, resident’s relations with their landlord,

and lessons learnt.

“Involve residents from the beginning of the design and development

process. Organise a professional design team. Go for the option of full

improvement rather than second best. Concentrate resources initially on a

few tower blocks rather than spread them thinly over many. Give others a

definite timetable for when their turn will come. Specify that the

principal building contractor appoints a liaison officer to work with

tenants representatives for the duration of the contract.” (Case Study

prepared by Geoff Green, Sheffield Hallam University as part of the WHO

(EURO) Healthy Cities Project.)

Reference: http://www3.iclei.org/egpis/egpc-059.html

Woolton, Liverpool, Guinness Trust

The Woolton Project was initiated by the Liverpool Housing Action Trust to

redevelop its existing high-rise tower blocks in the Woolton area of

Liverpool. This project reports strong performance in terms of residents’

choice and involvement, and in design standards. The estate is home to a

stable population of tenants, the majority of whom are over 60, with a

strong neighbourhood identity.

The first phase of the project included the demolition of Linksview Tower

and redevelopment of the site. An extra care scheme was built to act as

the community hub, delivering services to its residents and the tenants of

the wider community. Also at Linksview is a modern, fully equipped

community centre, which is run by a committee of tenant representatives. Work commenced on the first block, Lymecroft in February, 2003. When this

is completed the pre-allocated tenants and leaseholders will then move

back to their fully modernised and refurbished flats. A percentage of

these flats will be fully adapted to disabled standards, with a further

percentage developed to Lifetime Homes standards.

All flats will meet Secure by Design standards and, where practicable will

also meet the Housing Corporations Scheme Design Standards. Continuing

with Phase Two the Trust will undertake the refurbishment of a further

three of the remaining high-rise blocks, the final block at Valeview will

be demolished and the land offered for sale by Liverpool HAT.

Decision making at Woolton has been borne out of a very comprehensive

consultation exercise. A new forum was convened, The Design Advisory

Group, met fortnightly with the Trust and the Architect (Webb Seeger

Moorhouse), to discuss in depth various design options and formulate the

tenant choice programme for the whole of the estate. The tenants and

residents have also been involved in the selection and commissioning of an

Art Project. The contract for Phase Two is being undertaken by Brammall Construction

Limited via a Partnering Arrangement, utilising a PPC2000 Partnering

Contract to encourage innovation. The total refurbishment programme is set

for completion by the end of 2006.

Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council Tower Block refurbishment

The refurbishments feature a number of measures in line with environmental

sustainability, including installation of photovoltaics.

Tenants were allowed to select from a list of kitchen and bathrooms

designs and were also to benefit from new floor coverings. To reduce noise

transfer a sound insulation system was installed to the whole floor area

to alleviate impact noise. Security has also been considered with new

front doors to the flats and an entry phone system to the main entrance

door with a camera linked to the tenant’s television sets. Fire safety has

been improved with a remote monitored fire detection system in addition to

smoke detectors in each flat. As part of the SUREURO project SMBC and BRE

are planning to monitor energy usage, indoor environmental quality,

household waste and water use in the flats.

In addition to the refurbishment of the two tower blocks most of the

original housing stock is being demolished to make way for new housing.

Part of the redevelopment is to include a group of ‘intelligent and green’

houses, as part of the Integer Project.

International projects

Residential Complex, Toronto, Ontario

The owner of a two-tower, 30+ year old residential apartment complex in

Toronto, confronted with rising electricity and heating costs and high

maintenance expenses for the existing boiler system, decided to install a

co-generation system. This system would reduce electricity costs by

generating electricity on-site and applying the accompanying heat to space

heating and potable hot water heating. The owner aimed to reduce

electrical operating costs, and protect himself against anticipated

increases in electricity prices. He also wanted a system that would

provide a simple payback of less than four years, as well as equipment

with a long working life and reasonable maintenance costs. A co-generation

system would address these expectations.

A co-generation system is an electrical-mechanical system that

simultaneously produces both electricity and heat. It uses the heat that

is normally rejected by an electrical utility both at the plant and in the

transmission system. Electrical utilities discard 70 per cent of the

fossil fuel energy they consume, compared to 10-30 per cent for a

co-generation system. This offers significantly improved energy efficiency

compared to conventional building energy systems that use electricity

supplied by a utility, generated by combustion of fossil fuels.

Jack Satter House, Boston U.S.A.

Jack Satter House is a seniors complex, housing more than 500 residents in

266 units. The 1979 building is located on the ocean front at Revere Beach

near Boston,

Massachusetts. In 1994, after fifteen years of occupancy, the

outside cladding had seriously deteriorated and required total

replacement. The premature deterioration was a result of deficiencies in

the original design combined with ocean front environmental exposure. Massachusetts. In 1994, after fifteen years of occupancy, the

outside cladding had seriously deteriorated and required total

replacement. The premature deterioration was a result of deficiencies in

the original design combined with ocean front environmental exposure.

The retrofit was to proceed under several conditions:

• The undamaged interior gypsum board finish was to be kept intact

• There was to be minimal displacement or disturbance of the residents

• The new cladding system was to remain virtually maintenance free for 25

years with a minimum life span of 40 years

• All components were to be well suited for an ocean front environment

• Existing asbestos panels were to be removed and safely disposed of

Sheathing on the exterior face of the steel studs as well as the

insulation between the studs was removed. Corroded studs were reinforced

and/or removed as required and new sheathing on the exterior face of the

steel studs was installed. A peel and stick asphalt membrane was then

introduced to form a new air/vapour barrier. Galvanized subgirts were

installed by fastening them through the membrane and sheathing to the

supporting steel with stainless screws. Three inches (76.2 mm) of extruded

polystyrene insulation was added to achieve R15 (RSI 2.64).Where required,

new aluminium windows and a cladding/window interface were installed.The

final step was to introduce an innovative rain screen: a pressure

equalized cladding of aluminium plates was added as the visible exterior

element.

Gårdsten Estate, Göteborg, Sweden

The Gårdsten is a large Swedish housing estate built in the 1970s. The

estate consists of three five-to-six storey southfacing apartments, and

seven three-storey apartments, six facing east/west and one facing south.

As the physical condition and social environment of the buildings had

deteriorated considerably over the years, a comprehensive refurbishment is

underway for 255 of the 1000 apartments in the estate. (A less

comprehensive renovation is planned for the remaining apartments.) The

European Union (EU) is subsidizing the installation of solar energy

technology, including the replacement of one conventional roof with

integral solar collectors, under the THERMIE program.

The Gårdsten retrofit focuses principally on addressing problems that have

resulted from poor maintenance work over the years; and on the

incorporation of innovative energy technology. Following extensive

examination of renovation and energy retrofit options in 1997-1998, energy

measures were selected based on their potential for both energy and cost

savings. Construction began in 1999; the first block was commissioned in

early 2000, and the whole project is scheduled for completion in 2001. The

comprehensive retrofit is intended to help reduce the large vacancy rate

and to improve the social environment in the housing estate.

The Ballymun housing estate Dublin

The Ballymun housing estate was built during the mid-1960s and is located

in Dublin. The project encompasses 2,820 dwellings in 7 fifteen storey, 14

eight storey and 10 four storey buildings. Dublin Corporation is the owner

of the estate, while Ballymun Regeneration Ltd. (BRL) is managing the

refurbishment process.

The aim of the project is to revitalize a run-down housing estate,

implement low energy measures to provide affordable warmth for the

occupants and provide employment opportunities for the residents.

The district heating system will be replaced by condensing gas boilers,

which will also heat the domestic hot water (DHW). Heat will now be

controlled in individual homes by thermostatic radiator control valves

with a room thermostat and programmer. The addition of trickle ventilators

will aid natural ventilation. 10 timber-frame dwellings will be

super-insulated and triple-glazed. 70 of the dwellings will be equipped

with passive ventilation and a further 70 with gas fires will be fitted in

30 dwellings. Active solar water heating will be introduced in 10

dwellings. Electric heat-pump heating will be installed in 10 dwellings.

All dwellings will be equipped with condensing gas boilers. 10 units will have dual flush toilets. Small-scale demonstration and monitoring will

ensure the successful integration of innovative technology.

San Cristóbal de los Ángeles

San Cristóbal de los Ángeles is a dense, run-down urban area of Southern

Madrid.

The project consists of the environmental refurbishment of 72 apartments

located in two social housing blocks built between 1951 and 1960. Block

212, containing 48 apartments, is oriented East-West while Block 5110,

containing 24 apartments, runs on a North-South axis , so a variety of

solutions are expected from the international design competition. All the

apartments have individual owners and the project is managed by Empresa

Municipal de la Vivienda (EMV), through its Office of Innovative

Residential Schemes. The project consists of the environmental refurbishment of 72 apartments

located in two social housing blocks built between 1951 and 1960. Block

212, containing 48 apartments, is oriented East-West while Block 5110,

containing 24 apartments, runs on a North-South axis , so a variety of

solutions are expected from the international design competition. All the

apartments have individual owners and the project is managed by Empresa

Municipal de la Vivienda (EMV), through its Office of Innovative

Residential Schemes.

Passive solar measures include the addition of glazed balconies and

thermal mass. The thermal Energy savings of between 40 and properties of

the facades will be improved by the installation of low emissivity (low-E)

glazing in good-quality frames, high quality insulation and an exterior

ventilated skin. High quality insulation and a ventilated cavity will be

built into the roof, while an integrated flat plate solar collector

(around 3 m 2 /apartment) will provide domestic hot water (DHW). A

collective condensing gas boiler will replace individual butane-fuelled

stoves, and radiators will be installed in the apartments. The existing

individual butane/propane fuelled heaters for DHW will be replaced with

solar collectors and a collective heater back-up system derived from

natural gas sources. Energy efficient luminaires and low water consumption

fittings will be installed.

|

introduction

|

state of the art |

sustainability |

|

|

|

As indicated by the term “double-skin” such a façade is intended to mean a

system in which two "skins" - two layers of glass - are separated by a

significant amount of air space, that is to say, a second glass façade is

placed in front of the first. These two sheets of glass act as an

insulation between the outside and inside enabling the air to circulate

between the cavity of the two facades skin providing good air circulation,

thermal and accoustic performance, etc. The type of double-skin façade

then determines the type of air circulation. Of course, the most

interesting systems are those designed in such a way that in addition to

permitting natural air circulation, they also use solar energy, converting

it into electrical energy.

As indicated by the term “double-skin” such a façade is intended to mean a

system in which two "skins" - two layers of glass - are separated by a

significant amount of air space, that is to say, a second glass façade is

placed in front of the first. These two sheets of glass act as an

insulation between the outside and inside enabling the air to circulate

between the cavity of the two facades skin providing good air circulation,

thermal and accoustic performance, etc. The type of double-skin façade

then determines the type of air circulation. Of course, the most

interesting systems are those designed in such a way that in addition to

permitting natural air circulation, they also use solar energy, converting

it into electrical energy.  ater', and is the opposite of

'hydrophobic' (water-repellent). That makes water droplets spread out,

across the surface of the glass. Basically, it means water spreads evenly

over the surface of the glass to form a thin film that washes away and

dries off quickly without leaving unsightly 'drying spots'. Hydrophilic –

water attracting - coatings can be photocatalytically active and break-up

organic dirt, which can be washed away by the water-sheeting effect on

hydrophilic surfaces. Hydrophilic coatings are mechanically much more

stable. They face challenges by metal ions from rainwater poisoning their photocatalytic activity over time and some also exhibit a certain

colour

tint.

ater', and is the opposite of

'hydrophobic' (water-repellent). That makes water droplets spread out,

across the surface of the glass. Basically, it means water spreads evenly

over the surface of the glass to form a thin film that washes away and

dries off quickly without leaving unsightly 'drying spots'. Hydrophilic –

water attracting - coatings can be photocatalytically active and break-up

organic dirt, which can be washed away by the water-sheeting effect on

hydrophilic surfaces. Hydrophilic coatings are mechanically much more

stable. They face challenges by metal ions from rainwater poisoning their photocatalytic activity over time and some also exhibit a certain

colour

tint.

The project consists of the environmental refurbishment of 72 apartments

located in two social housing blocks built between 1951 and 1960. Block

212, containing 48 apartments, is oriented East-West while Block 5110,

containing 24 apartments, runs on a North-South axis , so a variety of

solutions are expected from the international design competition. All the

apartments have individual owners and the project is managed by Empresa

Municipal de la Vivienda (EMV), through its Office of Innovative

Residential Schemes.

The project consists of the environmental refurbishment of 72 apartments

located in two social housing blocks built between 1951 and 1960. Block

212, containing 48 apartments, is oriented East-West while Block 5110,

containing 24 apartments, runs on a North-South axis , so a variety of

solutions are expected from the international design competition. All the

apartments have individual owners and the project is managed by Empresa

Municipal de la Vivienda (EMV), through its Office of Innovative

Residential Schemes.